– my mentawai family –

a personal story

I made further discoveries in these islands, where I found a population more likable still and, if possible, still more ingenuous. If I continue in this direction, I may expect somewhere to find the "Garden of Eden", and descendants of our first parents.

Sir Thomas Raffles – 1821

Dedicated to the late Aman Patre, Mentawai shaman

It’s about time…

I’ve been told to write about my experiences and life with my Mentawai tribe family for so long, and by so many… In fact, ever since I returned from my first trip to Siberut Island, back in 1990. And I kept telling them and myself that I should, and “one day” will. But I kept postponing this for more than two decades… Somehow I didn’t see much point in writing about my own experience for people I don’t know, or who may simply not be very interested anyway. And the people I do know and who do care have heard me telling about my time with the Mentawai already so much… Over the last 30 years I’ve also brought my parents, my son, my wife and quite a few friends and other genuinely interested people to my Mentawai family. And more friends, family and other interested people will follow. So why should I write about this…? And for whom…?

And now I know.

Life is changing for my Mentawai family, as it has changed for the majority of the Mentawai people already much longer ago. Of course change is inevitable. Some call it evolving, or at least adjusting to a changing environment. What I see as an enormous challenge though is the speed at which the environment is changing. Not all generations of the Mentawai are able to cope with this speed of change. Others are not willing to adjust, or evolve. The younger generation naturally welcomes change, as it provides new opportunities for their future. Ambitions grow. The older generations are often far less interested in such new opportunities. And they have never learnt to be ambitious. That’s just not how they grew up, and being ambitions has never been part of Mentawai culture. The Mentawai way of life has always evolved around the community, not individuals.

Today the changing environment of the Mentawai is pulling generations apart…

I tried to ignore this growing challenge for a long time. Perhaps I pretended that time would continue to stand almost still, in what Sir Thomas Raffles described so well as the “Garden of Eden”. Deep in my heart I wished that I wouldn’t have to witness this change myself. But today I do not only witness this change, I am increasingly being involved in it by my Mentawai family. After all, I am part of the family, and their community. Different generations ask me questions that I sometimes find hard to answer, at least not without being biased. Parents as well as kids share their thoughts and concerns, and ask for advice…

What can I do? What should I do..? Should I do something at all…? Am I going to witness the end of traditional Mentawai culture as it has been for thousands of years, in just a matter of 2 generations…? This thought makes me incredibly sad. It touches my heart deeper than I could ever imagine and just writing this makes me cry… Do I just observe?

I cannot just observe… I’m one of them! I belong to their Uma, their community, ever since the late Aman Patre adopted me as his son, now 30 years ago. The entire family considers me as a full blood-relative. That’s Mentawai culture. And the uma, the community, comes first.

So I have decided that I will not just observe. I have decided to actually continue to contribute to the community, the uma. As that is exactly what they expect from me, now more than ever before. I will do this to the best of my ability, following my own experience, judgements and consciousness…! I owe this to my Mentawai father, the late Aman Patre, not only a great Mentawai shaman, but most of all a fantastic human, husband and father. I owe this also to his wife, Teteu, my Mentawai mother. An amazing woman who was left alone too early to raise their 6 surviving children. Children who I call my brothers and sisters: Aman Manja, Aman Sasali, Bai Jalamati, Bai Baguli, Lily, Kakui.

So this writing is therefore no longer going to be just about my own experience and how wonderful everything has been. Yes, the first part will be, as I’d like to share how the relationship with my Mentawai family evolved over time, and about how I see and experience the Mentawai. Why today they still mean so much to me, more than ever before. But eventually I want this to be for them, and by them. I want my Mentawai family to explain the struggle they face today. How THEY see themselves, the changing world and their future. This will be THEIR story, and the story of their children.

I hope you enjoy learning more about the Mentawai!

Toine IJsseldijk

This link will go to my dedicated website about THE MENTAWAI

Before I start my story, first a short historical background about Siberut Island and an introduction to the indigenous Mentawai tribe and culture.

About Siberut

The Mentawai archipelago lies about 130 – 150 kilometers west of the coast of Sumatra and consists of about 50 islands, of which only the four largest, Siberut, Sipora, North- and South-Pagai are inhabited. Siberut is the largest of the islands, with an area of 4480 km2, a little smaller than for instance Bali.

The east coast of Siberut, facing the mainland of Sumatra, runs slowly down into the sea and is relative easy accessible. The sea is mostly quiet and there are many bays, separated from each other by white sandy beaches and mangrove forests. On the east coast there are 2 main harbors, Sikakap in the north and Muara Siberut in the south, and these 2 harbors are the main gateway to the island’s interior. As a contrast, the west coast forms the westernmost edge of the Asian plate and the coast drops steep into the Indian Ocean, continuously exposed to the force of waves coming all the way from Africa. There are no harbors on the west coast, and this has kept the interior of western Siberut fairly isolated, until today.

There are no mountains on Siberut and the highest elevation is only 384 meters. The upper-layer of the soil is poor in rocks and therefore very soft, allowing a tremendous erosion throughout time and resulting in sharp-edged hills, steep slopes and a countless number of small streams winding their way to bigger rivers. Closer to the coast the meandering rivers form broad valleys and fertile earth deposits on the riverbanks and in the marshy lowlands. Here is where the majority of the Mentawai live, in their traditional long-houses dotted along the rivers and its tributaries.

The population density on Siberut has remained low throughout time and it is estimated that there are only about 20,000 Mentawai living on the island. That means an average only about 5 inhabitants per km2!

The Mentawai Islands are not only unique for its culture, but also its biodiversity and wildlife. The islands have been separated from the mainland of Sumatra for over 500,000 years, and it is estimated that 65% of the animal species are endemic, meaning they do not exist anywhere else in the world! Rather unique for relative small islands…

The origin of the Mentawai

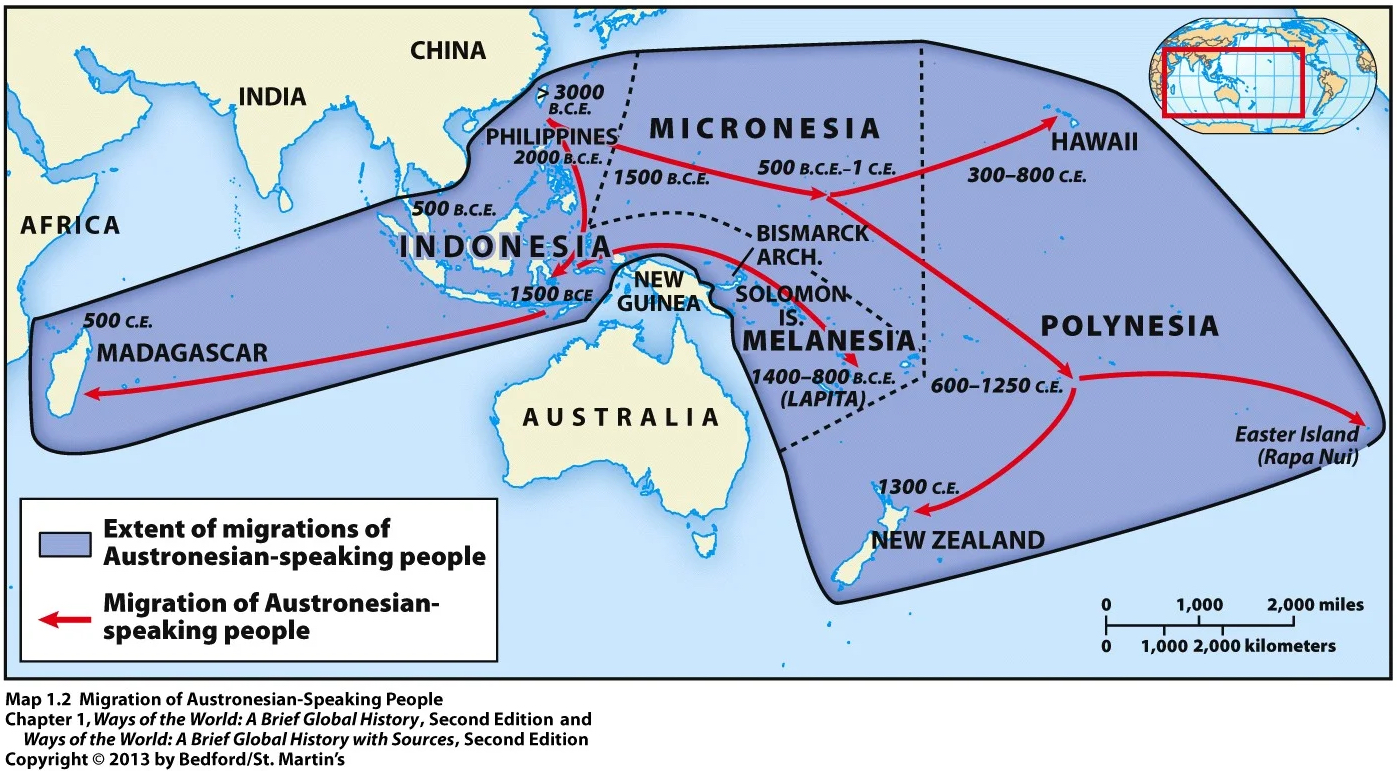

It is currently estimated that the Mentawai ancestors arrived on the islands between 2,000 and 500 BCE (Before Common Era). The Mentawai are Austronesian people, originating from coastal China and modern-day Taiwan. Around 4,000 years ago the Austronesians went on a sea-borne migration in their huge canoes, traveling south and east, populating the Southeast Asian and Pacific islands. These people belonged to the Mongolian race, speaking dialects of the Austronesian language-group. They were farmers, keeping chickens and pigs as pets, but they did not know the rice-culture yet. Their main tools were axes with a stone blade, which until recently have been used in Polynesia and even Indonesia (Irian Jaya) and which have also been found on Siberut.

The culture of the Mentawai people is rooted in the late Neolithic era, shaped by Stone Age traditions with traces of early metalworking. Around two thousand years ago, the islands felt the distant influence of the Dongson culture—an early Bronze Age civilization centered in what is now northern Vietnam. This wave of innovation brought rice cultivation, the domestication of water buffalo, new weaving practices, and the skill of working with metal to parts of Indonesia.

On the Mentawai Islands, however, this influence remained faint. Aside from the arrival of a few metal tools, daily life continued much as it always had. Isolated from the outside world, the Mentawai maintained their independence from foreign societies and cultures. It is this long-standing separation that has preserved the authenticity of their traditions, making their way of life both rare and remarkable today.

Change…

The Mentawai islands became part of the Dutch East Indies in 1864. Initially the Mentawai reacted with a lot of resistance towards policies imposed on them by the Dutch, including “pacification”. Eventually the Dutch accepted the Mentawai traditional way of life, including the great rituals, and did no longer attempt to meddle with the day-to-day lives of the Mentawai. Journals written during this period talk of ‘flower-adorned’ natives and time being spent ‘with the amiable savages’ on ‘the island of happiness’ (Maass, 1902, Karny, 1925).

The Mentawai islands became part of the Dutch East Indies in 1864. Initially the Mentawai reacted with a lot of resistance towards policies imposed on them by the Dutch, including “pacification”. Eventually the Dutch accepted the Mentawai traditional way of life, including the great rituals, and did no longer attempt to meddle with the day-to-day lives of the Mentawai. Journals written during this period talk of ‘flower-adorned’ natives and time being spent ‘with the amiable savages’ on ‘the island of happiness’ (Maass, 1902, Karny, 1925).

Following in the footsteps of the Dutch were the first Christian missionaries. They had quite opposite thoughts and the early protestant missionaries disapproved and looked down upon the indigenous community for their superstitious beliefs, rituals and cultural behaviour, describing the people as ‘lazy, underdeveloped and stupid’ and having ‘the distress of a poor people trapped in the terror of evil’ (Hammons, 2010). The first missionary was killed by the Mentawai and eventually also the influence of the first missionaries was minimal; at the beginning of the Second World War only 10% of the population was Christianized.

The first serious attack on the traditional Mentawai culture came after Indonesian independence. By that time also the Catholic missionaries had settled on the island and in 1954 a government decree prohibited animist religions. All Mentawai had to decide within 3 months to join either Christianity or Islam. If no decision was made, one was threatened by either religion-teachers or the police and religious objects of the Mentawai were burned. A cultural genocide, which targeted particularly the Mentawai shamans.

Over the following decades the government simultaneously began introducing development programs designed to integrate the Mentawai into mainstream society and to concentrate the Mentawai, who lived scattered in the forest and river-valleys, into newly established government villages. They were forced to live in houses of one-family unit, in ‘decent’ villages, with a church and a school. The long hairs and loincloths of the men and other traditional garb were prohibited, as well as the sharpening of teeth and tattooing of the body, all signs of ‘indecent primitivism’. The general aim of this policy was to combat “backward (primitif) thinking and practices” in order to promote “development”.

What seemed like a hopeless situation during the 1980s slowly started to change. The policy of resettlement was slowly relaxed. In 1981 Unesco declared the entire island of Siberut a Biosphere Reserve, as 65% of the animals on Siberut are endemic. Early 1990s plans to develop the rain forests of the Sakuddei into a palm oil plantation were abandoned and also logging started to be better controlled. In 1994 almost half of Siberut became a new Indonesian national park, under supervision and support of both the Indonesian government as well as local and international organizations. Tourism was slowly developing, supporting a slow revival of the Mentawai culture and traditional way of life.

Major successes still have to be realized, but at least more serious people are now involved in thinking about the future of Siberut, its forest and both the modern as well as the traditional Mentawai. Unfortunately most of the damage has been done, and the number of indigenous people still actively practicing the Mentawai cultural customs, rituals and ceremonies had already been limited to a very small population of clans, primarily located around the Sarereiket and Sakuddei regions in the south and west of Siberut Island.

The Uma – a house

The traditional Mentawai do not live in villages, but in impressive communal houses where up to 10 patrilineal related families might live together. Both these communal houses as well as the related families living there are called Uma.

The umas are built on riverbanks, until deep in the interior of the island, at the edge of the forest where rivers are just small creeks. Usually the extended families of a clan built their uma in the same area, in a small cluster, with each uma at least a few hundred meters away from the nearest neighbouring uma. Different clusters of umas are usually a few kilometers from each other.

Traditionally an uma is between 20 to 30 meters long, 6 to 10 meters wide and about 5 meters high. It is built on stilts, about a meter above the ground. The uma’s roof is made from palm leaves and is reaching almost to the floor. If well maintained, an uma might last up to 50 years, although today’s newer built umas may only last half that age.

The uma is divided in several spaces, each with a different function. At the front of the uma you have the porch: an open platform in front of the actual entrance. Then a large roofed veranda, which is where the Mentawai hang out to socialize with each other as well as visiting guests. Then the entrance to the first and largest interior room, with usually a central fire place.

The front of this first room is almost always open, but can be closed by 3 large hanging doors, which only happens when the entire community is going away for a few days, for instance to attend a ceremony in a far away uma. This largest room is used for the main ceremonies, cooking of sacrificed pigs and chicken and is also where the men, older children and guests sleep. At the back of this first interior room is a single door, leading to the second and smaller interior room, which has 2 open fire pits against the back wall. This room is where most of the meals are prepared and where the women and young children sleep. It is also the room where the most sacred rituals and ceremonies are held. At the back of this second room is another door, leading to a small platform outside, used for washing dishes and other household work. Along the sides of the uma are a few other doors leading to smaller platforms, all used for a variety of purposes.

The Uma – a community

An uma is a small village under a single roof. The members of an uma help each other in their daily lives, in a non-hierarchical community based on solidarity and equality, without any kind of leadership and with equality among men and women. The Mentawai have a strong sense of community and each family is subordinate to this community. Within an uma decisions are made together, in communal meetings.

Each household within an uma is in principle self-supporting and man and woman together are able to produce everything needed for a traditional life. As soon as children are old enough they will help their parents as well. The sons inherit the property of their parents, while the married daughters will join their husbands’ uma.

Each household within an uma is in principle self-supporting and man and woman together are able to produce everything needed for a traditional life. As soon as children are old enough they will help their parents as well. The sons inherit the property of their parents, while the married daughters will join their husbands’ uma.

As long as a girl is not yet married her brothers have to take care of her.

For the Mentawai it is not the family, but the local group, the uma, which is the actual unit in which daily life is lived and a lot of work is done together. This is because a single family is simply too limited to manage daily life. For heavy work they often need help from others, and when somebody falls sick or when a parent dies it is almost impossible for the rest of the family to take care of each other. Also children are raised not only by their parents, but all adults in an uma.

Daily Life

Traditionally the Mentawai do not struggle to maintain and support themselves and food is almost the last thing to worry about. They are completely self-sufficient, as they get all they need from their plantations and as hunter-gatherers from the river, the forest and the sea. The island is scarcely populated and most soil is very fertile, which makes growing crops relative easy. Sago, taro and bananas make up their staple food, and is supplemented with the meat of domesticated pigs and chickens and that of wild animals caught in the jungle, rivers and sometimes ocean. The jungle also provides a huge variety of other edible and useful products.

Work-techniques of the Mentawai are simple and food production as well as preparation is uncomplicated and not very work-intensive. The Mentawai do not know specialization in work, although not everybody is as skilled as others in the different kinds of daily work. Work is only defined by gender and evenly divided between men and women. The reason for this gender-related differentiation in work is mainly a matter of the differences in strength. Women also tend to focus more on work in or near the uma, as they also have to look after the children when the men are working further away in the plantations or forest.

As soon as children are old enough they will help their family: the sons will help their older brothers and father, the girls will help their older sisters and mother. Together they produce everything necessary for life.

Sometimes the Mentawai visit the coast, in their large canoes, for fishing or trading with settlers from Sumatra or even Java. The Mentawai themselves traditionally never settled along the coast though, as salt seawater flows at high tide up the rivers, making the riverbanks far from attractive for settlement.

Sometimes the Mentawai visit the coast, in their large canoes, for fishing or trading with settlers from Sumatra or even Java. The Mentawai themselves traditionally never settled along the coast though, as salt seawater flows at high tide up the rivers, making the riverbanks far from attractive for settlement.

In the forested steep hills of the interior the only way of transport is by foot, along a network of small, sometimes hardly recognizable trails and countless stream beds. When rivers are large enough the Mentawai use their long dugout canoes (abak) to transport products from the forest or their small plantations back home, and occasionally to the coast to sell or trade. In the lowlands rivers are almost the only arteries used for transportation of both goods and people, as large coastal areas in the east are covered by mangrove or swamp, making any form of land transport almost impossible.

Agriculture

Upstream from the Mentawai settlements, where rivers get smaller and land more hilly and forested, the Mentawai exploit the forest and lay out their agricultural fields, small plantations. Each family within an uma has its own fields and this is also where they have their own small house, the sapou, where they raise their pigs and chickens.

After a few years, when the soil of a plantation is losing fertility, they plant fruit trees. Where used to be rain forest they create their own new production forest, from which they can harvest more food than from the original rain forest. Further inland these production forests give way to almost unspoiled tropical rain forest. The Mentawai use these original forests only extensively, for collecting firewood, trees for their canoes or houses, rattan and occasionally they go there to hunt for wild game: pigs, deer or monkeys.

The main staple food of the Mentawai is sago, flour from the grated stem of sago palms. Sago palms are growing in patches in the swampy marshland, called mata: ‘eyes’. Each patch of palms has an owner; either he who planted the first young sago palms of the patch or he who got the patch through heritage or as gift.

The main staple food of the Mentawai is sago, flour from the grated stem of sago palms. Sago palms are growing in patches in the swampy marshland, called mata: ‘eyes’. Each patch of palms has an owner; either he who planted the first young sago palms of the patch or he who got the patch through heritage or as gift.

A sago palm needs at least ten years to become fully grown. The swamps where the sago palms grow are very fertile, because of a continuous supply of minerals from the little streams from the hills or regular flooding. Sago palms produce their own young shoots, so if a sago patch is well maintained it effectively can produce food for decades. The entire process, from planting young palms to the actual making of sago-flour is mainly men-work and done in these swamps.

First the palm is felled and the very hard bark is opened and pealed off with machetes and a large palm wood chisel. Then the soft core of the sago palm is grated with a large wooden rasp with nails. The raw sago pulp is collected in large baskets and then processed in what I call a small ‘one-person-sago-flour-factory’ (pasirereat): a large sieve built on stilts above an artificial small pond in a small creek. The sieve is traditionally made of bamboo and the fibers of palm leave shafts.

The sieve basket is filled with raw sago pulp and one of the men will then stand in the sieve, repeatedly scooping water from the pond with a kind of bucket attached to a long pole, pouring the water over his thighs while rhythmically stamping around through the pulp. Quite a unique sight, almost like a dance!

The water, with the dissolved fine sago-flour, drains through the sieve into an old dugout canoe. The sago-flour then slowly deposits at the bottom of the canoe, while excess water slowly flows over the edge of the canoe. After a few days the flour is collected and then stored in meter high cylindrical containers, made of sago palm-leaves tied together with rattan. The containers with sago-flour are then stored under water, where the flour remains good for months.

Sago-flour is one of the world’s most time-efficient staple foods to process. It takes the Mentawai about 5 days to process a fully grown sago palm, and the palm can produce up to 500 kilo of dry flour. For an ordinary family this is enough for a couple of months. Usually, different families cooperate in the processing of sago and the flour is then shared.

A sago palm or parts of it can be used in many other ways. Sometimes a sago palm is felled and then split open along the entire stem. The soft core of the palm is then accessible for the sago-beetle (tamara), which lays her eggs inside the sago. A month later the Mentawai then collect the thumb-sized larvae of the sago-beetle from the half-rotten palm. These grubs are very rich in protein and eaten alive, boiled or roasted.

The leaves of the sago palm are also used to make atap for the roofs of the uma, while the shaft of the leaves are used to make suitcases (bakulu), baskets and sleeping-mats.

Another important food-source for the Mentawai is the root of the taro. Taro is grown in the muddy wet fields close to the rivers, usually close to the uma or a sapou. The taro fields and the entire process from planting to harvest is the women’s domain of work and every women has her own taro field, sometimes a few. To protect the taro against pigs the fields are surrounded by a large natural fence. After each harvest the soil is plowed and then planted again. The fields can be used years on end, as they are naturally fertilized by flooding rivers or streams.

At the higher land around the taro fields, where the soil is more dry, different species of banana trees, other root-crops and sugarcane are grown. All these crops are planted and harvested throughout the year and do not depend on any season.

Banana trees are planted on the dry banks of the rivers as well, by both men and women. A banana field does not require much maintenance work and a fence is also not necessary. Older trees produce young shoots and a banana field can be productive for many years.

New fields for agriculture are prepared in the forest by a man and his wife together, usually not far from their sapou. First they clean the ground from the lower vegetation and small trees. Then usually young banana trees and sweet potatoes are planted, between the remaining trees of the forest. After these crops start to grow the remaining trees of the forest are felled. In contrast with other tribes in Asia which practice slash and burn techniques, the Mentawai do not burn the vegetation or felled trees, as this is considered a waste. Instead, they let it decompose.

When the leaves and other green of the cleaned vegetation and felled trees are decomposed they plant additional crops, such as a kind of taro that grows in dryer soil, tapioca, papaya, chili, turmeric and sometimes pineapple, cucumber, tobacco and plants used for making poison for the hunt. Once the banana trees grow big enough and produce sufficient shadow, seeds of slow growing fruit trees are planted, for instance durian, jackfruit, rambutan, lemon and others.

Over the next few years the family can harvest and replace the ‘dry’ taro, tapioca, fast growing fruits like pineapple and papaya, but over time the soil gets exhausted. Then the Mentawai do not plant new crops anymore and only look after the slow growing fruit trees. Some of these fruit trees start to produce fruit within a couple of years, but durian for example only after ten years or more. The plantation has now changed into a new kind of productive forest (mone), from which the family can regularly harvest the different kinds of fruits for many years to come.

Another daily Mentawai food item is grated coconut. Men grow coconut palms on the dry river banks near their sapou, but also far away up or down stream the river.

Another daily Mentawai food item is grated coconut. Men grow coconut palms on the dry river banks near their sapou, but also far away up or down stream the river.

On Siberut each coconut palm has an owner and the same rule as for other fruit trees counts: if you are traveling and are thirsty you can take a coconut, but it is a serious crime if you harvest with the intention to bring back home or sell.

Stealing coconuts used to be one of the major crimes on Siberut, because coconuts were excellent to barter or sell to settlers in the harbors, to obtain for example iron tools, glass beads and fabrics. Nowadays more forest products are sold in the harbor, like rattan and bananas.

The Mentawai use the coconuts also for other purposes. From the nut they make spoons and they used to make a traditional tobacco container, which they hung around their waist with a piece of rope. From the fibers of the coconut peal they make thick rope, used for fishing nets that are used at sea. This rope is also used for carrying their bugbug, a bamboo tube in which the men keep their poisonous arrows for the hunt.

Livestock and Pets

The Mentawai breed chickens for the meat and for sacrifices. Especially during large ceremonies dozens of chickens are sacrificed. Chickens are rarely kept for the eggs alone, because the Mentawai see that as a waste: each egg produces another chicken, resulting in more eggs than the one where the chicken came from…

Chickens are usually kept at the sapou of the family, or dedicated chicken shelters. The chickens are regularly moved from one to another sapou, so they are able to find fresh food and also to make it harder for predators such as snakes to find them. During the day the chickens are left to roam free, looking for their own food. Each afternoon chickens with chicks are locked up in a rattan basket and are fed grated sago and coconut. In the morning they are fed again and then released.

The most important livestock for the Mentawai are the half domesticated pigs. They are mostly left to roam free, but at least every few days the pigs are additionally fed with sago, either near the uma or a sapou. Feeding the pigs is, as for the chickens, done by both man, his wife and the older children.

The pigs give birth in the forest and are not kept separate. Within a month the piglets start to eat independently.

Pregnant female pigs usually bite and chase away the boars and when the majority of females are pregnant the free roaming boars might run away to other feeding sites to find more females or, more dangerous for the owner of the pigs, to the pigs of another uma or even search for a wild herd of pigs. The Mentawai have an effective solution to avoid this: when most females are pregnant, all the present boars are castrated. Castrated boars don’t run away anymore, and another advantage is that these boars become more fat and grow up to eighty kilos. As young male pigs become sexual active within a year there is never a shortage of reproductive males.

Pigs fulfill an important position in the spiritual world of the Mentawai and breeding pigs is therefore surrounded with taboos. When a female pig is visibly pregnant, up to the moment the piglets start to eat independent, it is for instance taboo for the owners of the pigs to plant crops, have intercourse or be deloused.

Pigs are also the most important asset for the Mentawai and having many pigs increases an uma‘s prestige in the valley. Special guests for instance, can be welcomed with the preparation of a young pig. The adult females and large castrated males are solely reserved for communal celebrations and ceremonies of the community. Each time pigs are sacrificed all relatives and friends living in umas nearby receive meat as well, all in equal portions. The more meat, the higher the prestige of an uma.

Pigs are also the Mentawai’s strongest currency. When somebody is in need of something, whether goods or services, it can be bought with pigs. Pigs are therefore also a fixed part of the bride-price and return-gifts during weddings. Pigs are also sacrificed for the creation of new friendship relations with for instance other uma. Finely, during traditional healing ceremonies it is impossible to reconcile the spirit of the sick person with the spiritual world of the beyond without sacrificing pigs.

Other pets that are held are dogs and cats, probably introduced by early traders.

Other pets that are held are dogs and cats, probably introduced by early traders.

Dogs are the only animals on Siberut that have names. Yet, life of the dogs in the uma does not seem to be a lot of fun. Dogs are not fed and have to look for their own food. They are therefore always hungry and often beaten when looking around for food in the uma or trying to steal some. They have to sneak around, without drawing attention and probably that is the reason that within the uma dogs not even dare to really bark. Only outside during a hunt the dogs show their real character and most uma have a few dogs trained for hunting. Good hunting dogs are popular and often get extra food and even sometimes join the owner on a longer journey.

Cats are mainly held to keep rats at bay and are therefore rarely fed. Cats are generally more popular than the dogs and rarely beaten when stealing some food…

Hunting

The Mentawai men and boys regularly go out hunting, either to just find food to complement their daily staple food, or as part of larger ceremonies, which often include a traditional hunt. Main game is wild boar, deer and monkeys. Smaller animals like squirrels or hornbills are shot as well. Of the four primate species that live on the Mentawai Islands only the bilou, a gibbon-species, is taboo, probably because of its likeness with humans. The Mentawai have different hunting techniques, depending on what animal they hunt. Most animals are hunted with bow and arrow, but spears are also often used for wild boar and deer. Usually specially trained hunting dogs join the hunt as well.

The bow (rourou) is made of the hard wood of an aren-palm, polished with stone and leaves. The bow’s string is usually made from twisted bark strips of the baiko, a kind of breadfruit tree. It’s bark is also used to make the traditional loincloth of the shamans.

The arrow shafts (silogui) are made of a kind of elephant grass, which usually grows along the forest edges. The tip of the arrows are made of palm wood or brass.

The shape of the arrow-tip depends on the target. For monkeys for instance, the tip is carved halfway and breaks when the monkey tries to pull out the arrow after being shot. This then allows the poison to be released into the monkey’s body and take effect. For squirrels the arrow-tips are not poisonous and also not carved. The weight of the arrow will simply exhaust the fleeing wounded animal, which eventually will just fall out of the tree. For deer and wild boar tips of brass are used, which penetrate the thick skin more easily. For smaller birds arrows with a thick tip are used, in order not to penetrate the small animal or ruin its feathers, which are often used for ceremonial decorations.

The tips of the arrows used to hunt monkeys, boar and deer are smeared with a few layers of poison (ragi) and then stored and carried in a container (bugbug). This bugbug is made from a bamboo tube, covered with a sheet made from the shaft of a sago palm-leave, for protection against rain. A thick rope made from coconut husk is attached to carry the bugbug.

The Mentawai have several recipes for poison and ingredients are either grown around the uma, at the plantations or they are found in the forest. The poison paralyses the nerve-system of the animal and works within a few minutes. The most commonly used poison is made from the leaves of ipuh, a small bush. The leaves are first cut with a machete and then grated on the spiny shaft of a palm tree. On a special wooden plate the leaves are then crunched with a wooden mortar, together with a piece of tuba root and chili. The chili stimulates the blood flow after an animal is shot and speeds up the poison’s effect.

Another kind of poison is made from a special liana. The bark of this liana is grounded and then prepared in the same way, with tuba root and chili as well.

This poisonous mixture is then put in a small hand-sized donut-shape basket made of rattan, and is then pressed and squeezed with a wooden press. The sap is collected in a coconut-shell and then heated up in a piece of bamboo. The poison is then ready to be applied on the arrow tips.

The arrows are then warmed up above a fire, to speed up the drying of the poison. This process is repeated several times, in order to get enough poison on each arrow tip. Also old arrows are treated again, because over time the poison looses its strength.

The preparation of poison has to be done outside the uma. The souls of previously caught game, living in the skulls on display in the uma, should not be made aware of the preparations for a hunt, as they may warn the souls of their living relatives. The hunt will then often fail.

Arat Sabulungan

This is the official name of the Mentawai believe, although the Mentawai themselves do not use this name. Arat Sabulungan translates as “Believe in the Leaves”, referring to the many different kinds of leaves that play such an important role in their spiritual lives.

The Mentawai believe that everything that exists has a soul (simagere): not only people, but also the animals, plants, rocks, objects and even temporary phenomena like the rainbow or clouds. Souls are created together with their visible body, but at least the souls of people will live forever. The souls roam around freely in their own realm, but there is a continuous link between a soul and its earthly body and body and soul influence each other both ways.

What the human souls experience during the night will be seen in their dreams. But also the mind and feelings during daytime are related to the experiences of the souls. When roaming around in their realm, souls are exposed to each other and they are able to influence each other. For example, during the ceremonial preparations of a hunt the Mentawai try to attract the souls of game to their uma, by offering to the souls of previously caught animals, of which the skulls hang in the uma. These skulls are cleaned and nicely decorated, in order to make them attractive enough for their souls to live in. By offering to these souls they are invited to convince the souls of their living family and friends to come to the uma as well. If the souls of game feel attracted they will allow the hunters to catch them, so their souls will be reunited with the souls of family and friends.

The interactions between body and soul might also lead to dangerous situations. When a soul roams around in its realm and meets with something evil it will also have a harmful effect on the body of the soul. The way this works has to do with what the Mentawai call bajou. The bajou is a power, a kind of radiation that is released by everything that has a soul. It varies in intensity, depending on the nature of its owner. The bajou itself is neither good nor bad and normally not a threat. However, when different bajou with different intensities meet each other too sudden, a negative or even catastrophic effect on the soul might be the result. For instance, supernatural creatures from the world beyond have a very strong bajou and are potentially dangerous.

For the Mentawai life is therefore about maintaining a harmonious balance and good relationships with the souls. If a soul is disregarded or ignored it may feel distressed or flee away. A tool or activity may fail. Or its human body will get sick. This is what the Mentawai fear most… As once a human soul has been welcomed by the souls of their ancestors, decorated itself in their presence and eaten together with them, then the time has come to die.

Care for your Soul

To stay in close touch with one’s soul, a Mentawai has to live a beautiful life that makes his soul happy, strong and resistant. It will assure that the soul will stay in his neighbourhood and not roam away to the dangerous unknown. Good food, flowers, jewelry and other decorations and an overall good physical appearance is what the souls like. The human soul also likes a relaxed lifestyle, and this is why one of the most often used expressions on Siberut is “moile, moile”, “slowly, slowly”. It is a very bad manner to ask a Mentawai to hurry; souls do not like their bodies to rush around or act recklessly. They also do not like to force somebody to do something.

To further strengthen the bond with their souls the Mentawai will regularly dance, make music and sing to the souls during ritual ceremonies.

The human souls also expect their human body to follow codes of behaviour and a diverse range of taboos, to maintain harmony amongst the bodily world and the world beyond.

An important taboo for instance, is used during all preparations for a hunt: it is strictly taboo to eat anything sour. Sour and sharp are related to each other: you might injure yourself with the sharp arrows or knifes. Another example is the prohibition to be deloused when you have a pig with young. The comparison is obvious: the piglets might get lost like the lice, picked from one’s hair and thrown away. Another example is the taboo for men to make a dugout canoe while their wife is pregnant. The hollowing out of a tree trunk is not compatible with the pregnancy of his wife and might lead to a premature abortion and the canoe will not be a success.

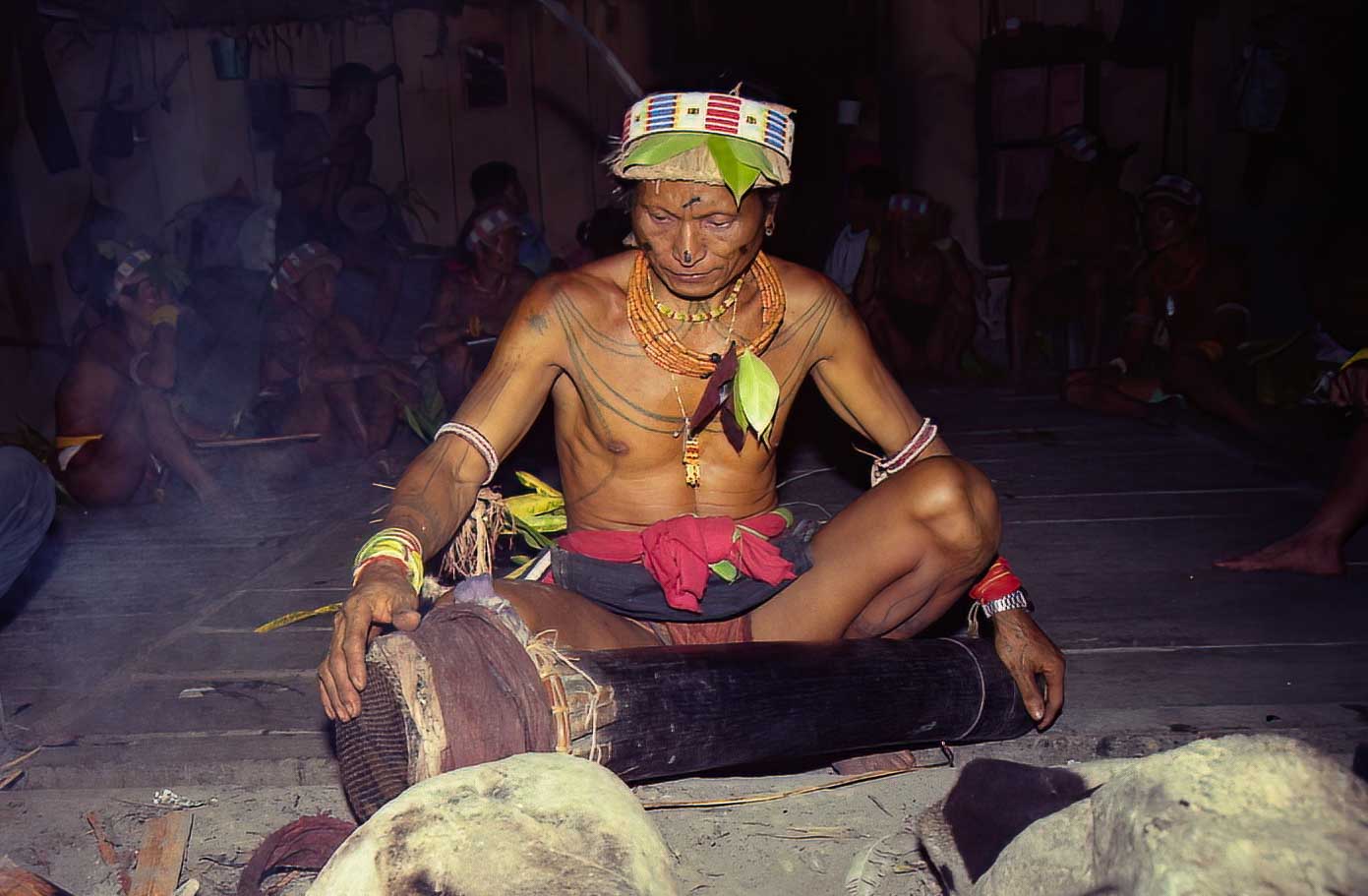

Shamans – Kerei

The most impressive manifestation of the Mentawai culture is the shaman, the kerei. The shamans are the only Mentawai who have their own domain of work. First of all they are medicine-men, the herbal doctors of the Mentawai. They are able to fight diseases which cannot be cured by anyone else. Second, the shamans have the ability to communicate with the world of the beyond, with the souls. Healing ceremonies almost always revolve around the reconciliation of a patient’s soul with its earthly body.

One of the Shaman’s most important skill as a mediator is that he has ‘seeing eyes’, and is able to see the souls, ancestors and other spirits during visions. The shamans seek these visions during during ceremonies or other important rituals, through trance-inducing dances and sacred kerei songs.

The ‘seeing eyes’ of a kerei are received as a favor from the world beyond, as signs of appreciation for the many sacrifices made during the ceremonies that are part of becoming a shaman.

To become a kerei is a choice, and a lifelong commitment. It comes with great respect, but also a lot of responsibilities, and taboos. If he does not follow. the taboos he will not only jeopardize the success of healing, but his own soul as well. Being a kerei does not improve one’s economical situation and there is no personal profit from healings. The compensation for healings is only a larger share of the meat of sacrificed animals, and this has to be shared with the entire community back home. But because of their skills and powers the shamans often stand in the middle of attention and belong to a respected elite.

Longing for a respected name is therefore often the main motive for someone to become a shaman. Fathers also often encourage their sons to become a shaman, because this enhances his own reputation as well. A respectable kerei initiation requires the sacrifice of hundreds of chickens and dozens of pigs, mainly contributed by the father. For this he is praised throughout the island.

Up to a third of the grown-up men in a valley might be shaman, although nowadays the interest to become a kerei amongst the younger generations is rapidly declining.

Although the wife of a kerei usually does not participate actively in healing ceremonies, she has to obey certain taboos during these periods as well. Sexual intercourse, cultivation of crops and fishing for instance are taboo, and the kerei and his wife are only allowed to take minimal care of their domesticated animals. Only at some ceremonies the wife of a shaman might assist her husband with the blessings as well.

To become a kerei requires a learning period of several months, called the Pukereijat. More about that later.

Mediators

Mentawai shamans often bless objects, souls or even activities. For a blessing words alone are not enough. To be able to communicate to the souls, the shamans have to use a bridge between them and the world beyond, where the souls live. The shamans use a diverse collection of specific plants as well as pigs and chicken as mediators, called gaut, to cross this bridge. According to the Mentawai, the plants’ and animals’ souls are able to ‘send’ the blessing to the realm of the souls. Different plants and animals have different functions.

The Mentawai use hundreds of plant mediators, which often can be used in many different ways. They distinguish between “bad” mediators, able to counter evil, and “good” mediators, able to attract the desirable. Often a relation exists between the shape of the plant and its function as bridge to the souls.

Pigs and chickens are usually “good” mediators, for instance to attract the souls of wild game, before a hunt. What distinguishes pigs and chickens from the plants is that a possible success of their negotiation can be seen directly in the intestines of the sacrificed animal. After a blessing, the animal is killed and cleaned. On the membrane between the intestines of a chicken the shaman can ‘read’ a message from the world of the beyond: whether the animal managed to send the blessing message or not. For a pig the hart is used to read this message. If the result is not favorable the entire procedure is repeated, hoping that the next sacrificed animal is a better mediator…

Fetishes

The magic plants which the shamans use for a single negotiation or blessing can also be used for a long-term influence on the world of the beyond. For this purpose the magic plants are turned into a fetish during a special ceremony, as a small bunch or package, wrapped in a piece of cloth and tightened together with some rattan.

The magic plants which the shamans use for a single negotiation or blessing can also be used for a long-term influence on the world of the beyond. For this purpose the magic plants are turned into a fetish during a special ceremony, as a small bunch or package, wrapped in a piece of cloth and tightened together with some rattan.

These fetishes are carefully kept, because they keep their power as a mediator. For instance, for a newborn child and its parents a fetish of different mediator plants is made to protect the child during the first few months of life.

As everything else that exists, a fetish has its own soul and at the end of a rituals sacrifices are made to the new fetish as well.

The most important fetish for the Mentawai is the bakkat katsaila, the main fetish of each uma. When the building a new uma has finished a new bakkat katsaila has to be made. It is then blessed and, as a new object, has now its own soul. The bakkat katsaila‘s soul becomes the main protector of the uma: it keeps away ‘evil’ and attracts ‘good’ at the same time.

The bakkat katsaila is hanging from the main pole of the uma, inside the back room, on the left side of the door when facing the uma’s entrance. It is a large collection of different mediator-plants, placed in a large traditional basket. At every ceremony sacrifices are made to the bakkat katsaila and more mediator plants added, to manage a good relationship its soul and strengthen it.

Care for the Environment

Because all that exists is alive through its soul, connected and communicating with each other, the Mentawai believe that therefore everything is and has to be in balance with each other; one harmonious environment. However, people are forced to interfere in this harmony, because every worldly activity effectively changes the spiritual balance of the environment. This interference is potentially dangerous: if the balance is disturbed the person concerned might become the victim.

The way the Mentawai deal with this dilemma is through continuous reconciliations. With each worldly activity the Mentawai have to consider its possible influence and impact in the world of the souls. This impact might be dangerous, but also very useful; through blessings the Shamans try to manipulate the outcome of activities in the world beyond, by continuously reconciling the souls of the people, objects and activities involved.

Without such reconciliation an offended soul might take revenge. Often the way to reconcile is directly related to the activity, for instance when a pig or chicken has to be sacrificed. The Mentawai will explain to the pig or chicken why he has to be killed. They will remind the pig or chicken about the care and good life they have received, and will cool down the pig or chicken’s possible anger with blessings.

PUKEREIJAT – BECOMING A SHAMAN

The training of a novice begins generally after marriage and is under the supervision of a ‘master’ from another uma, the paumat, usually an uncle, but never the novice’s father. Usually a few novices are trained together, by a few different paumat. For his commitment and dedication the paumat is generously rewarded with pigs and various other gifts and the growing bond between the paumet and the eventually new shaman also bring families of different umas closer together.

During the course of the novice’s training to become a shaman five major ceremonies take place, spread out over a couple of months. During these ceremonies non-relevant work is taboo for the entire community and preparations such as making of sufficient sago flour, collecting plenty of fire wood and bamboo for cooking is done all well in advance.

The first ceremony is called Tadde, a festive evening that kick’s off the training. On the evening of Tadde the uma is ritually cleansed and the spirits are summoned. Evil spirits are driven out with a kind of ceremonial whip (nangaingai), made of tree bark and different kinds of leaves. The shamans dance all night long to the rhythms of the traditional drums (kajeuma). The kajeuma is a set of three or four different sized drums, made of palm wood (paddegat) and covered with python skin. Before the drums are played they are heated near the fire, to tighten their python skins. Most Mentawai dances imitate animals, such as birds, butterflies and primates. The night climaxes with trance-inducing dances, when the shamans’ search for spiritual visions, communicating with the world of the beyond. In rare occasions also the wife of a shaman or even other members of the community might go into trance.

After this first communal ceremony the future shaman and his wife have to spend a couple of months in total seclusion, far away deep in the forest in a small dedicated hut (pulaeat). This hut is built by the novice himself, his wife and usually some other family members or friends. The pulaeat is initiated during an intimate private ceremony, with only the novice’s teacher, the paumat, the novice and his closest relatives. During this ceremony the ancestral spirits are informed about the new novice; they receive sacrifices and their help for a successful training is requested.

The initiation ceremony of the pulaeat introduces a period of strict taboos for the novice and his wife, until the final ceremony for the initiation of the novice as a new shaman. Over the next few months the novice and his wife will live a sober life, without any decoration. Their main duty is to raise chickens and pigs and cultivate decorative plants and flowers for the coming ceremonies.

The end of the novice’s period in the pulaeat is accompanied by the third communal ceremony, attended by all members of the uma and anyone else close to the uma‘s community. After this period of confinement and mental preparation of the novice the actual training starts. The paumat teaches the novice all the lyrics and melodies of dozens of shaman songs and chants, and the secret details of rituals which are exclusively known to shamans. Most of the shaman songs are in the ancient language of Simatalu, the place of origin of the Mentawai. This language is only known to shamans.

While the novice is learning, family and close friends make the traditional garb and accessories of the future shaman.

The most outstanding accessories of a shaman are a special head-band, the luat,

and the shaman necklace, the tudda. The luat is made of a strip of rattan, covered with white fabric and decorated with strings of small glass beads. Each clan has its own color pattern. The tudda is a necklace of cylindrical ocher-colored glass beads and usually a few of these necklaces are tied together.

The lekkau is a set of bracelets for the upper-arms, traditionally made of woven red-painted rattan and studded with strings of white glass beads. Over last decade or so the painted rattan is sometimes replaced with strings of red glass beads. The sabo is the dance-skirt of the shamans, made of different colored pieces of cloth and a woven rattan strip at the bottom, decorated with feathers.

The most important and powerful necklace of a shaman is the abak ngalou, made of a strip of woven rattan and decorated with glass beads, with different fetishes hanging underneath. The jarajara is a special decoration for the hair, made of the ribs of sago palm leaves and feathers, with a fetish as well. Shamans also wear a special red loincloth (kabit), made of the bark of a special tree, baiko. The softened bark is colored dark red-brown by soaking it in sap from the bark of a special mangrove tree (toggoro). The entire outfit of the shaman has partly a spiritual and partly decorative meaning. According to the shamans, souls and spirits in the world beyond can only be influenced or communicated with when they meet worthy opponents.

On the second festive night, Sigeugeu, the novice receives spiritual power from the ancestral spirits, while dancing around an elaborately decorated small tree (kinimbu), which is placed next to the uma.

The novice’s training continues, accompanied by regular pig sacrifices.

On the night of Lecu the novice is fitted with a magical anklet of woven rattan, for bodily protection. For the first time they are able to dance in the fire, without getting hurt. The evening is followed by Sigepgep, a night of silence and darkness.

A few months pass. Then is the time for the novice to receive his ‘seeing eyes’. At a secret pool at a hidden location deep in the forest the novice has to swear not to reveal this most intimate secret of the kerei. The novice then gets a splash of a magical potion in his eyes, and he becomes ‘seeing’; from now on he is able to see the souls and spirits of the world beyond. This event is then followed by the culmination of the actual initiation as a kerei: Alup. Huge bamboo poles are erected at the river bank, one for each pig sacrificed during the novice’s learning period. The poles are decorated with sago palm leaves and wood carvings of birds, humans and fish, hanging from the top of the bamboo poles. Similar wood carvings are also hung above the entrance of the uma, to welcome guests, spirits and ancestral and human souls. These wood carvings are called umat simagere, ‘toys of the souls’.

Early in the evening the largest pigs are sacrificed, to commemorate the ancestors. Before the pigs are cooked they are first tied to a large pole and hung above the floor. The shamans then take their youngest children and bless them while running underneath the sacrificed pigs, a ceremony called abimen. A great communal meal follows, with the rimata, paumat, novice and other shamans of the uma and their wives, all in full festive attire. In the evening ceremonial decorations and attire, fabrics and tobacco are laid out on the uma‘s veranda and the ancestral souls are invited to take as much of it as they like. The novice, who now has ‘seeing eyes’, dances around and when the ancestral souls for a split second do not pay attention the new shaman charges forward and grabs a fetish from them. These fetishes are then attached to the shaman’s abak ngalou and a night of traditional dancing starts. Many guests from other umas come to this great event, including other shamans, for whom the other festive nights are taboo.

The shamans dance like birds, fully dressed with their traditional attire with flowers and decorative leaves mimicking feathers. The novice has his body and face dyed yellow with ground turmeric (kiniu). The climax is in the predawn hours, when the lajo-t-abak is danced, the dance of the canoe. The shamans dance anti-clockwise around in a circle, with the rimata holding a small model canoe in his hand, riding the waves and singing about a journey to Pageta Sabbau, a famous mythical kerei with extraordinary powers.

The rimata then sits down in front of the fireplace, personalizing Pageta Sabbau. The novice now dances a part of a bird-dance, but this time without the accompanying rhythm of the drums.

The soul of Pageta Sabbau is invited to come to the uma and give some of his powers to the novice. The novice sits in front of the rimata, who asks the last few questions to test the novice. When the questions are answered correctly the rimata blows in the ears of the novice, to give the novice the power to hear the souls. Suddenly the novice can see the soul of Pageta Sabbau, hovering above the rimata. Powerful fetishes (sineru) hang from Pageta Sabbau‘s head decoration (jarajara). With two hands the novice tries to grab one of the fetishes. He is instantly thrown backwards and crashes to the floor and is overcome with spasmodic fits. His eyes are rolled back, his body sweating and shaking vigorously. Other shamans now jump in and hold tight the novice, to stop the spasmodic fits, while chanting the novice back to consciousness. The shamans then open the hands of the novice, to see whether the novice succeeded to grab a fetish, as a sign of Pageta Sabbau‘s approval of the new kerei. This fetish gives the new shaman some of the powers of Pageta Sabbau and is added to his abak ngalou. If the novice did not succeed to grab a fetish he has to try another time.

The entire initiation ceremony of the new kerei ends with a traditional hunt for monkeys, deer and wild boar. These animals are considered as the domestic animals of the ancestors and their souls will announce whether or not they have accepted the offerings and approve the ceremonies. A successful hunt means they have given their blessings.