Sakuddei Clan - Siberut Island

The Mentawai Islands, West Sumatra - Indonesia

October 2024

The Mentawai tribe are the indigenous people of the Mentawai Islands, a small group of islands about 150 kilometers off the coast of Sumatra, in Indonesia. The Mentawai are renowned for their deep connection to nature and rich cultural traditions. Inhabiting the dense rainforests of Siberut island, a part of the tribe has preserved a way of life largely untouched by modern influences.

Known for their distinctive body art, including intricate tattoos symbolizing life, beauty and spirituality, the Mentawai people practice animism, believing in the spiritual essence of all living beings. Their traditional longhouses, or Uma, are communal spaces reflecting their emphasis on community. Despite external pressures, some of the Mentawai continue to embody resilience, fostering a harmonious relationship with their environment.

The Sakuddei Clan: Introduction

The Sakuddei are one of many clans within the Mentawai tribe, residing in the remote western region of Siberut Island, in a rainforest-covered valley named after the river they call home. Among the Mentawai clans, the Sakuddei stand out for preserving their traditional communal lifestyle. In the late 1960s, Swiss anthropologist Reimar Schefold, the leading authority on the Mentawai, spent several years living with the Sakuddei. His first major work on the Mentawai, published in 1979 in Dutch and German, was titled “Speelgoed voor de zielen: kunst en cultuur van de Mentawai-eilanden” / “Spielzeug für die Seelen: Kunst und Kultur der Mentawai-Inseln.” The English translation, “Toys for the Souls: Life and Art on the Mentawai Islands,” was only published in 2018 and remains the most comprehensive book about the Mentawai people.

The origins of the Sakuddei clan trace back to the Butui River valley, home to “my” Mentawai family. The Butui River is a small tributary of the Rereiket River, the largest river in Southeast Siberut. Today, this area hosts many of the last traditional Mentawai communities, scattered throughout the rainforest along the banks of the Rereiket and its tributaries. By the mid 1940s, the growing population along the Butui River began to strain local natural resources. Land for new plantations and space to raise pigs became increasingly scarce. In response, as is customary among the Mentawai, who are often described as “semi-nomadic”, some members of the clan decided to move to a new area to establish a new community.

During this time, three young brothers and their families ventured to the island’s southwest, a largely uninhabited region. After crossing the hills forming Siberut’s backbone, they settled along the Sakuddei river and named their newly founded clan after it. Today, one of the original members of this migration is still alive: Bali, now in her 80s, is one of the oldest living Mentawai, if not the oldest. More about her will come later…

I first visited the Sakuddei in 1995, accompanied by the late Domino, a close Mentawai friend whom I had known since my first visit to Siberut in 1990. Following that initial trip, I spent considerable time with a Mentawai family in Butui. As the Sakuddei trace their roots to Butui, clan members often visited, which is how I came to know them. In 1995, I decided to journey to the Sakuddei myself; a challenging trek on foot through the island’s rainforest-covered hills, followed by a canoe ride downstream along one of the Sakuddei River’s tributaries, which eventually brought me to the clan’s main Uma.

The Journey

Nowadays the Sakuddei can be reached by boat as well. I prefer the journey on foot though, as the rain forest on Siberut island is beautiful. But it’s a tough journey, and as we had limited time and a lot of film equipment we decided to charter a boat.

We departed from Muara Siberut, located on the island’s southeast coast, early in the morning to ensure we reached the west coast during high tide, the optimal time for a beach landing. The journey to Sagulubbek Beach on Siberut’s southwest coast took approximately four hours. Thankfully, the ocean remained relatively calm throughout the trip. The waters can become dangerously rough at times, making beach landings particularly hazardous…

Foreigners are a rare sight in this part of the island, though locals frequently use the beach near Sagulubbek to load forest products like coconuts and rattan onto boats, which are typically shipped directly to Padang. During certain seasons, local fishermen also catch significant amounts of fish and lobster along the shoreline, which are likewise transported to Sumatra’s mainland.

Upon landing on the beach, several locals appeared, along with a motorbike “taxi” for transporting luggage. We arranged for our luggage and equipment to be taken to the main village, located just a kilometer inland. From there, we planned to charter a large motorized canoe for the journey further inland.

Finding a large canoe took quite some time, as most boatsmen were working. So we had our lunch first and drank tea with some of the locals, before our boatsman finally showed up.

The journey upriver to the Sakuddei clan’s Uma typically takes around two hours, depending on water levels and currents. On the day we traveled upstream, the Sakuddei River was relatively high due to several days of rain. However, as the water level had begun to recede, the current was no longer particularly strong. This allowed our canoe to travel at full speed, making for a smooth and relatively quick journey.

As we traveled upriver, we occasionally passed small traditional houses nestled along the riverbanks. The river serves as the primary thoroughfare connecting scattered homes, plantations, and field huts. Most Mentawai still rely on traditional canoes for rowing upstream or downstream, as only a few can afford small outboard engines. Regularly, the Mentawai make their way downstream to Sagulubbek, transporting forest products to sell and purchasing basic necessities in return.

As we journeyed upriver, the initially flat landscape transformed into rolling hills. The expansive coconut and sago plantations gave way to increasingly dense rainforest. Along the way, I spotted a few kingfishers and even a couple of hornbills; birds that have become rare sights in eastern Siberut.

We passed the last small social village and entered the tribal lands of the Sakuddei. A familiar sense of belonging came over me: it felt like coming home. The scenery was just as I remembered it from 30 years ago. Another 10 minutes upriver brought us to the main Uma of the Sakuddei clan.

About 10 days earlier, we had managed to inform the clan of our intention to visit, though we couldn’t specify exactly when we would arrive. Remarkably, as if anticipating the precise moment, Aman Raiba, the owner of the Uma, arrived at the same time as us, paddling his canoe from further upriver. This wasn’t the first time I had experienced such uncanny timing. In the early 1990s, my late Mentawai father often knew exactly when I would arrive at his Uma, even when it was impossible to notify him in advance…!

We were warmly welcomed and quickly settled in. By late afternoon, some of the adult community members began returning from their scattered plantations and field huts, where they tended to their pigs. Most of the children were already home, though they remained shy at first and kept their distance.

After dinner, everyone in the Uma gathered around us to hear about our visit and plans for the coming days. We explained that we were working on a documentary about the Mentawai, and wanted to include the Sakuddei clan and the Uma, conduct some interviews and document wood carving traditions. The Sakuddei were once renowned for their wood carving skills, and Aman Jagaumanai kindly agreed to create a carving for us!

After a long day, it was finally time to rest. Following Mentawai custom, the women and young children slept in the back of the house, the men and young boys in the middle section, and we, as guests, stayed in the front section of the Uma. Our sleeping arrangements were simple yet familiar: a thin rattan mat beneath us, and a mosquito net overhead.

Here some of the members of the community:

The Uma

A Mentawai Uma is a traditional communal longhouse, and serves not only as a residence, but also as a cultural and spiritual center for the clan. An Uma is typically located in a forested area, close to a river or other natural resources, reflecting the Mentawai people’s deep harmony with their environment. It is elevated on stilts to protect against flooding, pests, and wild animals. Inside the Uma the space is open-plan, allowing for communal living and flexibility. It is also a sacred space where clan rituals, such as initiation rites, healing ceremonies, and animal sacrifices, take place. The Uma serves as a hub for social gatherings, storytelling and decision-making, but is also seen as a connection to the natural environment as well as ancestral spirits. The Uma is central to the Mentawai people’s animist beliefs.

In 1995, the Sakuddei Uma was located on the opposite side of the river. It was massive, the largest and tallest Uma I had ever seen. Several families lived together under its roof, spanning at least three generations and totaling a few dozen people.

The current Uma, however, is smaller and significantly lower in height. What stands out as unique now is the presence of several smaller houses built adjacent to the main Uma, with each family having its own separate dwelling.

Traditionally all members of the community, which could be 30 people or even more, would live in a single large Uma. That was still the case when I visited the Sakuddei back in 1995. But today the main Uma belongs to Aman Raiba, where he lives with his two wives and children. Aman Jagaumanai and Aman Tukulu, respectively the nephew and younger brother of Aman Raiba, have their own smaller traditional house, both adjacent to the main Uma. Bali has her own traditional house, a little further from the Uma. Two other nephews live a little further downstream: Aman Gabari Kerei and Aman Etteu, who nowadays lives in the nearby social village.

One of most impressive sights inside the Uma is the prominent display of the skulls of animals. There must be over a thousand skulls, of sacrificed semi-domesticated pigs and cows as well as from hunted game such as deer, different monkey species, wild boar and hornbills. Most skulls are decorated with dried young palm leaves and sometimes feathers, while the skulls of deer are also adorned with a carving of a bird or other animal. The decorated skulls have spiritual power and during ceremonies these skulls often become focal points, channeling ancestral and animal spirits to foster communal well-being.

When a Mentawai community moves into a new Uma the skulls of game are taken along and again displayed in the new Uma. The skulls of domesticated pigs are left behind in the old Uma, symbolizing the emphasis of the Mentawai people’s connection with nature.

From the color of the skulls in the current Uma it was very clear which skulls came from the old Uma: they were colored brown by the smoke of the fire pit in the central room of the old Uma. In the current Uma there is no fire pit in this room, so the skulls added in this Uma have remained much more light in color.

I was also particularly interested to see some of the typical shaman attributes of the Sakuddei, such as the salipa and bakulu. The salipa is a wooden box in which they keep their most sacred items such as fetishes and necklaces, but also bones, claws, or feathers from spiritually significant animals that are used for healing ceremonies. In the past the shamans would also keep small carved figurines, representations of ancestral spirits or protective deities, but most of the older items have now been taken by collectors and anthropologists… The bakulu is the shaman’s suitcase, and is made from the shaft of sago palm leaves. Here they store their loincloths, ceremonial attire such as feathers, beads, necklaces, shaman skirts and headdresses.

There used to be a lot of animal carvings in the wooden wall panels of an Uma, but nowadays they are fairly rare and are also carved much more rough than in older days.

Wood Carving

Aman Jagaumanai was ready to demonstrate his remarkable woodcarving skills. He selected a fresh piece of relatively soft wood, studied its shape, and began working with his machete. One section of the log became the bird’s body; another was reserved for its wings. The precision of each cut with the machete was astonishing.

Once the bird’s basic form was complete, Aman Jagaumanai used a traditional Mentawai tool called the balugui: a short, thin, but sturdy knife blade fixed to the end of a slightly bent piece of rattan. Slowly, the head, neck, tail, and wings took on more refined shapes. He carefully attached the wings to the body, finishing the piece with yellow turmeric and decorative lines of natural black paint made from a mixture of soot and oil.

In just two hours, Aman Jagaumanai transformed the wood into an intricately carved bird, a great example of Mentawai craftsmanship.

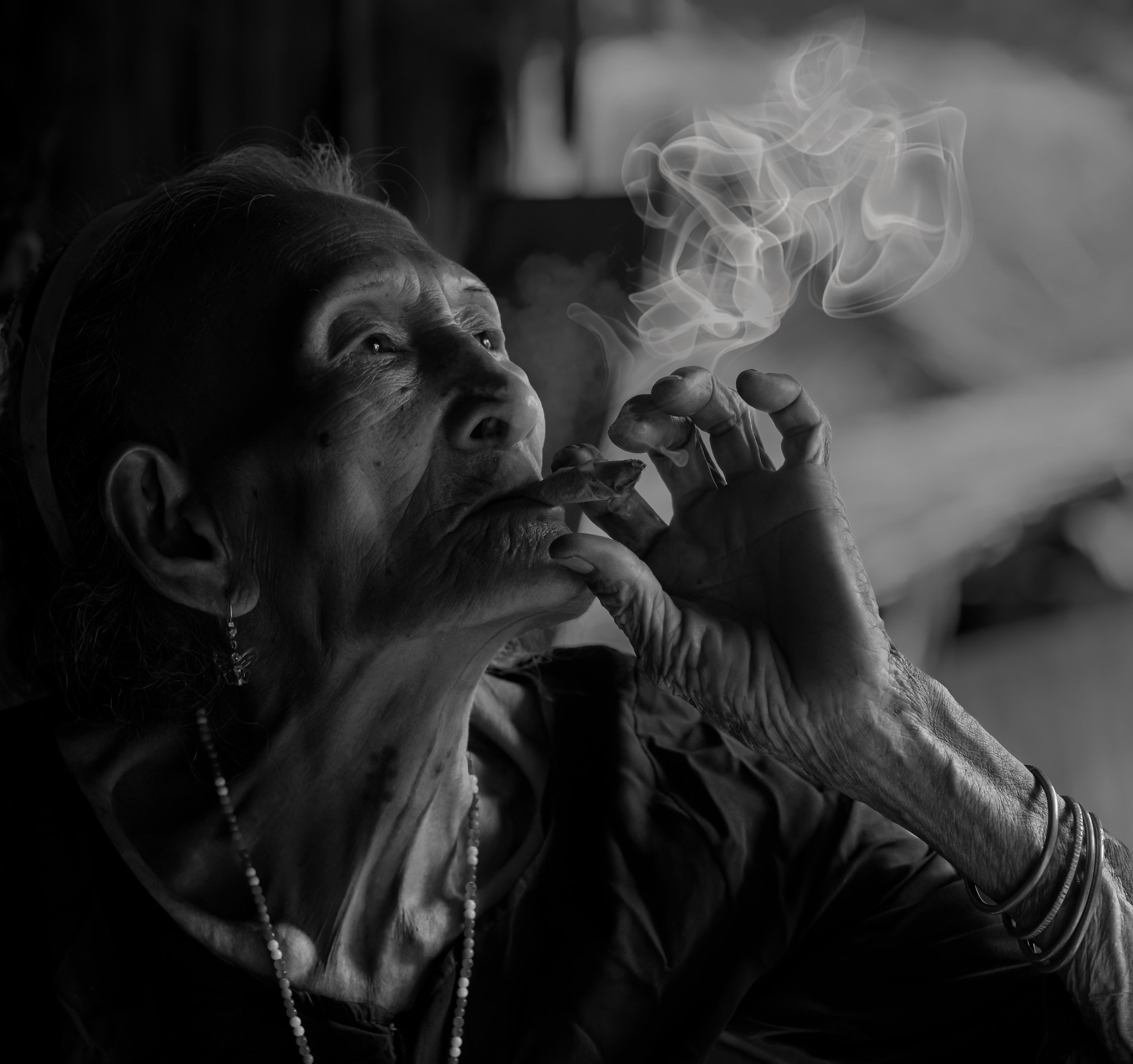

Bali - Elaugege

One of the interviews we were most excited about was with Bali, the eldest member of the Sakuddei clan. We were eager to hear her stories and learn about the past through her vivid recollections.

Bali is truly a remarkable character: witty, full of humor, and impressively energetic. She remains incredibly active, tending to her chickens and many of the pigs, and frequently paddles her canoe up and down the river to chop sago. She lives in her own small traditional house, which, by Mentawai standards, she keeps impeccably clean and tidy. Bali also loves smoking traditional tobacco, a habit she enjoys with her signature charm.

Bali was born in Butui, a river valley where my Mentawai family lives. At that time, her name was actually Elaugege. In Mentawai culture, names are often changed, such as when someone with the same name passes away or if a person experiences repeated misfortune or illness.

Bali’s father, along with his two brothers, decided that Butui had become too crowded. They resolved to move their young families to a new location to start fresh. Bali recounted how her father placed her in a rattan basket and carried her through the forest and across the hills of central Siberut toward the west coast, accompanied by her three older brothers.

The families eventually settled on the banks of the Sakuddei River and established a new clan, naming themselves the Sakuddei.

As a young girl, Bali grew up surrounded by her older brothers and nephews. She had a passion for hunting and always accompanied her father and brothers on their expeditions. Although, as a woman, she was forbidden from touching a bow and arrows, she was always ahead of the hunters, excelling at spotting monkeys and other game. Fearless, she would even chase wild boar toward the hunters.

Bali did not follow the traditional path of a young Mentawai girl and grew into a fierce, strong woman who intimidated every potential suitor; she never married…

Her three older brothers, however, married and became highly respected shamans, renowned throughout the island. Her eldest brother, the late Amandumat Kerei, was the father of Aman Raiba. Her second-oldest brother, the late Amanuisa, became a great Rimata, the tribal leader of the Sakuddei clan. He was the father of Aman Jagaumanai, who now holds the position of Rimata of the Sakuddei clan.

"Palu" The Hornbill

When we arrived at the Sakuddei, I noticed that Aman Jagaumanai kept a hornbill in a small cage. Although hornbills are protected, the Mentawai occasionally hunt them, displaying their distinctive bills inside the uma alongside the skulls of other game. However, I had never seen one kept as a pet before.

When I asked about the bird, Aman Jagaumanai explained that he had found it as a chick years ago and decided to raise it. They named the hornbill “Palu,” and it is now completely tame and appears very healthy. The bird is often let out of its cage, and one of Aman Jagaumanai’s daughters loves to play with it and even cuddle it!

Final Thoughts

We had an amazing few days with the Sakuddei, and I was overjoyed to finally visit them again. While things had changed over the past 30 years, the core essence of the Mentawai — living as a tightly knit, harmonious community — remained very much alive. It was a true pleasure to reconnect with Aman Raiba and Aman Jagaumanai, whom I hadn’t seen in years. They are both thriving, and it was inspiring to see them carrying forward the legacy of their fathers, the clan’s founders. And of course, it was a joy to meet Bali again; she is an incredible character, a truly unique Mentawai woman, and the embodiment of resilience.

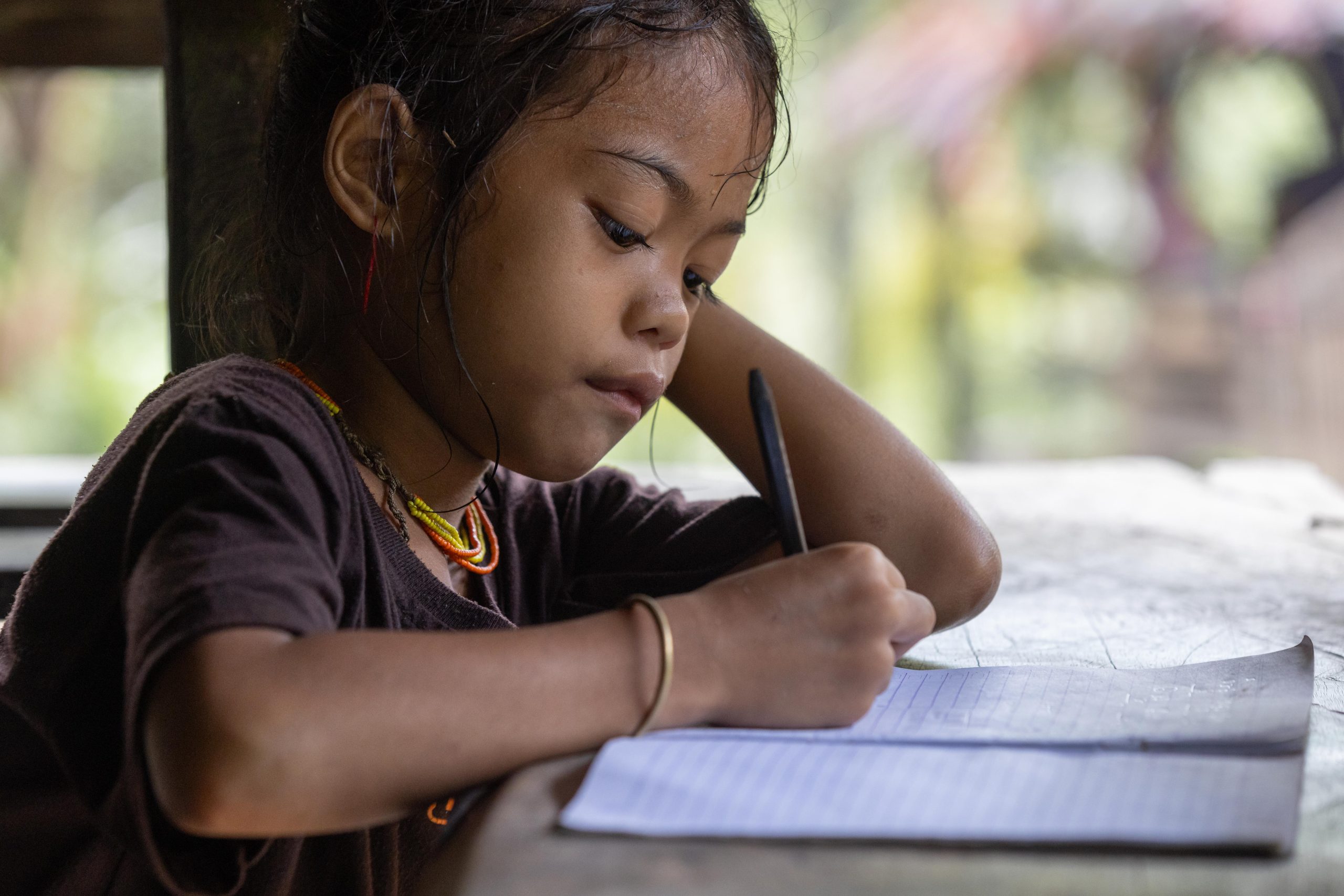

Today, the women and children of the Sakuddei wear shirts and shorts, and some of the other shamans have also moved away from wearing traditional loincloths in daily life. However, clothing changes don’t alter the deeply rooted Mentawai culture or the communal way of life. The children now attend school but remain actively involved in communal responsibilities. I hope they will continue the legacy of their parents in the future as well.

I look forward to one day attending a traditional ceremony at the Sakuddei, to witness their community in its full grandeur. That will be for another time! As I said in 1995, I’ll be back…!

Location MAP and GALLERY